A circular construction industry

Blunt forecasts on the way the world’s climate is rapidly changing have helped to reshape core ideas around the construction industry.

In keeping with the spirit of the age, the focus now is on ways to move from a wasteful, voracious linear model that generates a massive amount of greenhouse gas emissions to a circular construction industry where adaptation and reuse of materials is central.

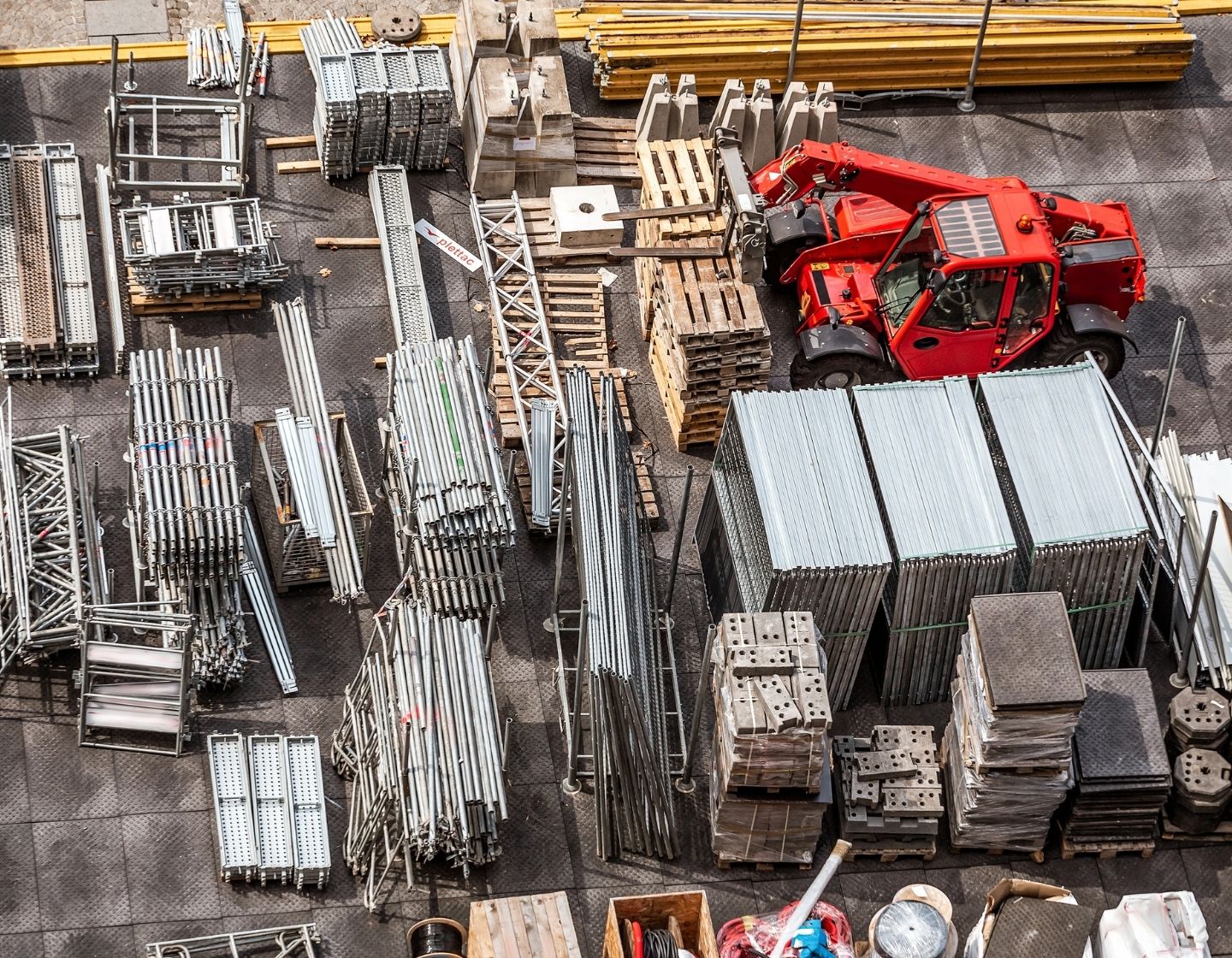

The circular construction industry concept imagines buildings as “material depots” that are stacked with a huge range of reusable resources to be utilised in new construction projects. How to achieve this planet-friendly revolution is work in progress.

The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) is developing practical guidance on implementing circular economy principles with the help of members and other stakeholders while also raising awareness and influencing government policy .

It advises that in the UK construction, demolition and excavation account for 60% of material use while generating a third of all waste and 45% of all CO2 emissions. On current pathways, material extraction will triple in the next 30 years and waste production will triple by 2100. Sector costs continue to rise and have reached a 40-year high, according to data from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICs).

Circular resources

The UKGBC believes that adopting circular economy principles offers a €1.8 trillion opportunity to the EU between 2015 and 2030. It launched its circular economy programme in Spring 2018, providing a growing range of resources on its website.

The concept of the circular economy is closely linked to the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and underpins the development of sustainable organisations. SaveMoneyCutCarbon is a part of this trend, with strategies that support many of the SDGs.

These interlinked global goals are a “blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all”. They recognise that action in one area will affect outcomes in others, and that development must balance social, economic and environmental sustainability.

Not surprisingly, it is a transformative move from the traditional linear economy. Our linear mode of production involves the mining of raw materials to make products that we throw away after use whereas in a circular economy, the cycles of these raw materials are closed, which involves more than just recycling. With this sustainable model, how value is created and preserved is completely transformed, with new business models developed around sustainable production.

Material depots

The idea of buildings being “material depots” comes from Dutch architect Thomas Rau. He says that “Waste is simply material without an identity. If we track the provenance and performance of every element of a building, giving it an identity, we can eliminate waste.”

He is developing a public database of materials in existing buildings and their potential for reuse, with more than 2.5m square metres of building matter recorded in the Madaster database. Rau is working with the Amsterdam authorities to catalogue the components of all public buildings in the city.

Buildings are registered using the Madaster digital platform, and details include the materials and products that were used in construction. Documenting, registering and archiving of the materials makes reuse easier while helping to facilitate smart design and eliminating waste. In this process, each building becomes a reservoir of materials.

Rau is aiming Madaster at owners of real estate and infrastructure as well as organisations working with them – architects, developers, contractors, engineers, deconstruction or harvesting companies and online marketplaces.

Material passports

He has developed the concept of a “material passport”, a digital record of the specific characteristics and value of every material in a construction project, so enabling the different parts to be recovered, recycled and reused.

As the construction process becomes more digitised, with the development of Building Information Modelling (BIM), the material passport is a layer of data that can be incorporated and tracked throughout a building’s life.

Madaster automatically generates secure, web-based passports for registered buildings and construction objects, which have information on the quality, origins and location of materials and products. The passport also gives insights on the material, circular and salvage value of buildings, which is a boon for property owners seeking to assess end-of-life value and ways to harvest this.

With the circular construction model, building depreciation (to zero) will become a quaint historical anomaly, and the ongoing value of a building is fully realised not just in the case of demolition or renovation, but also with new investments. According to Rau, the residual value of a building’s materials is around 18% of the original construction cost, negating costs of waste disposal at the same time.

World-first deconstruction

The database is not just wishful, blue-skies thinking. Rau put the principle into practice, with the design and construction of the new HQ for ethical bank Triodos in the Netherlands. It’s recognised as the world’s first completely demountable office building. The wood structure has mechanical fixings so that every element can be reused, with all material logged and designed for easy disassembly.

The European Commission is planning to introduce a “digital product passport” (DPP) in the coming months, with the aim of stimulating product reuse multiple times and proper recycling at the end of life. The DPP will give users more information about the supply chain of materials and products as well as most effective routing to waste management facilities.

The EU move is welcome and it is hoped that the UK and other countries will follow suit. As Pablo van den Bosch, who sies on the board at Madaster says, the greatest barrier is still “the limited willingness to demand a first step towards transparency by making it mandatory, from all key players in the industry: suppliers, buyers, regulators, etc.”

Leading the way is the Dutch government, which seeks to create conditions for a circular economy by 2050. It has created tax incentives for developers who register material passports for their buildings, and is considering making it a mandatory requirement for all new projects.

Across the European continent, there are a number of building projects that have embraced the re-use and logging model in some form.

Financial advantages

The financial sector has a positive view of the material passport, and can see the many benefits, from ensuring that product portfolios become more sustainable to heading off the threat of banks and investors holding stranded assets – products and materials that are not energy-efficient.

The Dutch bank ABN Amro, which has a €10.6bn commercial real estate portfolio, has clearly signalled its intention to maximise gains from the circular economy model, with its new Circl pavilion in Amsterdam, a showcase of circular construction principles. It views itself now as not just a financial bank, but a materials bank.-

One particularly stunning outcome of the thinking on circular construction is the vision of a future where every part of a building is viewed as a temporary service, rather than an owned object, and rented from the manufacturer. According to Rau, the producer would, in turn, be stimulated to ensure the best possible performance and effective maintenance, as well as managing end-of-life processing.

One element in the transformative move to circular construction that is urgently needed is a system whereby robust agreements that cover data security, privacy and trade secrets can be created between companies across the whole supply chain to allay concerns the passports holding data that would violate intellectual property rights.

The circular construction industry is a fundamental building block for the sustainable global economy, and a crucial element in the struggle to combat rapid, catastrophic climate change. It can’t come soon enough.